09.17.2020

Lessons in humility: Climbing Kilimanjaro

*This article was originally written in September 2016 immediately following this climb. It has been republished in honor of our 4-year anniversary of summit day.*

“Why do you climb this mountain?” I asked Little Man, an enthusiastic, yet slow-speaking porter nicknamed for his compact size. I was, of course, talking about Kilimanjaro.

“I want to make your biggest dream come true,” he said, turning to look at me with all-too-serious eyes. “If you reach the top, it makes us very happy.” Then he proceeded to pump water into my canteen with his bare hands, as he’d done every day after breakfast before hitting the trail, saving my fingers from the biting wind of Summit Crater Camp’s 18,700-foot elevation.

As a new porter on Mt. Kilimanjaro’s most dangerous Western Breach Route in Tanzania, Little Man had already made this climb 10 times — still paling in comparison to lead guide Ben’s 200-plus trips to the summit.

But this was my first time even venturing out of the United States, and after the fifth early morning of crawling from a tent into howling darkness up unpredictable inclines, I knew this was the craziest thing I’d ever done.

My dad, Steve, stepmom Tami, and I were on a mission: to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro in a fundraising campaign to raise $30,000 for the NRECA International Foundation’s rural electrification efforts in Africa and around the world.

We wanted to help “Electrify Africa” by joining the around 50,000 people who flock to Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa, every year in an attempt to cross “reach the 19,340-foot summit” off their bucket lists.

What the tour companies don’t tell you is that one-fourth of all Kili climbers don’t make it to the summit, and up to 10 die each year — not including those that go unreported — from altitude-related sickness, avalanches, falls, and heart attacks.

They also don’t tell you that your 10-person team’s success is largely dependent on 58 super-fit Tanzanian strangers: the cook staff, guides, and porters, who carry everything you need up and back down the mountain — mess hall and personal sleeping tents, chairs, food and water, and your precious 22-lb. duffle bag of cold-weather gear.

Even more unbelievably, the porters carry this 50-plus-pounds of baggage on their heads or necks, many without using their hands to balance the load.

Climbing the beast known as Kilimanjaro

We didn’t realize how diverse the landscape would be until it changed on us two days into the climb on the Shira Plateau. The breeze suddenly felt more like wind, and jackets were soon pulled over our sweaty T-shirts. We grew to despise the red, volcanic dust that blew around us like fog, making our noses run black.

But I was in awe to find that five different climate zones exist on the mountain, and nearly every type of ecological system can be found there: cultivated land, lush rainforest, heath, moorland, alpine desert, and an arctic summit.

By now, we could see Kili straight ahead, looming over us, its snowy top completely obscured by clouds — the place we were somehow supposed to reach in only a few short days. Looking the gigantic monster of a mountain straight in the eye was intimidating to say the least, and it took a toll on our confidence.

To our horror, on Day 4, my stepmom fell ill with what we believe was dust-induced bronchitis, hacking up so much phlegm she bruised her ribs. She refused to give up, but shortly after, we lost our first group member, Christine, who decided she couldn’t handle Kili or the constant shivering any longer. As I watched a porter escort her down the ruthless mountain out of sight, a deeper truth sank in: Victory here was more dependent on mental willpower than physical fitness.

Beware of falling rocks - and take your diamox

Green slowly faded from view and was replaced by slippery, brown-black volcanic gravel and enormous, speckled boulders. Day 5 was without a doubt the toughest and most dangerous test. A sign marked “Challenge Spot: Beware of falling rocks” even warned us as we approached the murderous Western Breach, jaggedly carved out over the years by melting glacier runoff and rock falls from above.

Just last year, a hiker was killed on the breach by a merciless rolling rock, and in 2006, three Americans were killed in the same fashion, but while sleeping in their tents. I told myself not to look up — no amount of neck straining would help me see the end goal in the clouds. It’s a miracle we were able to drag our swollen feet up to the next camp.

Those of us taking Diamox, an over-the-counter medicine to help prevent altitude sickness, were grateful not to feel overly nauseated, though many of us still had to pop an Advil nearly every day for headaches. By the end of Day 6, we kept to ourselves and moved like sloths, consumed with our own oxygen-deprived thoughts and why-am-I-doing-this-again questions.

We posed with the massive glaciers about 1,000 feet from the summit and then curled up in our sleeping bags as the wind howled and shook our tents violently. I prayed they would delay our final ascension climb; we can’t hike with wind like this…right?

Wrong.

Even after all we had been through, nothing prepared us for summit day. On Day 7, we woke by 4 a.m. and hiked ever-so-slowly up the slippery, narrow dirt path by headlamp. Though my helmet pinched my head, I was grateful for the added layer of wind protection.

Arriving at the summit during sunrise was nothing like I’d expected: insanely cold, crowded, and short-lived. International crowds lined up beside the Uhuru Peak sign, speaking languages indiscernible to me and seemingly incapable of taking turns for photo ops.

I snagged a few celebratory photos, hugged my family, and enjoyed the rich view.

But in the midst of the chaos, I crashed into the realization like a brick wall. This was the real deal, and somehow I was here in flesh and blood by the grace of God on the continent’s tallest mountain. I was nearly halfway around the world from home.

I was above the clouds, now only an ocean of mist beneath me. I’d never felt so in touch with nature as I did looking down from the top of Africa that day.

Then suddenly we were heading downhill — the more painful two-day segment of the trip nobody warns you about. Total muscle exhaustion is a real ordeal; our guide told us around 12 people a day have to be carried down in iron stretchers after their quads give out, no longer able to hold their own body weight.

I’d never hiked downhill for that many hours straight, and knowing now what each step does to your knees, shins, and calves, you couldn’t pay me to do it again.

Toes crunched into the front of your boots is not a pleasant feeling; my dad and Tami actually each ended up losing their big toenails as a result.

The unexpected takeaways of Kilimanjaro

It was during this tedious descent that my mind began to whirl. We had successfully reached the summit…but was it all really over, just like that? After all this time, the climax, the thing we had been working toward, was over in less than 20 minutes.

Ironically, my camera’s photos told a different story. The long-awaited summit photo — you know, the one that fuels your decision to buy the plane ticket in the first place — had turned out pretty lackluster with poor lighting.

Meanwhile, dozens of gorgeous landscape shots over the seven-day uphill trek were what struck a chord in me. I was preoccupied with making a trophy memory out of the summit, but what I didn’t realize was that each day’s photos were key memory bricks I had laid in time that together could be used to build an honest, more life-changing house of experience.

Yes, everyone knows the adage: The destination isn’t as important as the journey itself. The same was true of my Kilimanjaro adventure.

Hakuna Matata

Unexpectedly, the local people — especially the porters — were some of the kindest, most inspiring people I’ve ever met. Aside from being the key physical factor in our Kili success, the porters were also our cheerleaders, always passing our panting, weary team line with a “hakuna matata” — meaning “no worries” in Swahili — and an encouraging smile or sing-along song.

Nearly every morning, three porters, including Little Man, would knock on my tent door, too enthusiastically wish me a good morning, and serve hot coffee with milk and sugar. Insistent on helping and saving your energy, they refused to let me even strap on my own ankle gaiters.

I was at the complete mercy of these third world strangers for all of my needs, and watching them conquer the trail twice as quickly bearing five times as much weight in scanty hiking garb, flimsy jackets, and torn-out tennis shoes — all while focusing on getting me, a helpless tourist, to the top and down safely — was a slap-in-the-face dose of humility.

They were living examples that there’s no reason not to take the best possible attitude in any given situation, even when you aren’t sure of the outcome.

Funding Big Change

We knew our climb up Mt. Kilimanjaro would be tough, but we were fueled by the knowledge we were doing it for a good cause. Now, since fostering friendships with the locals, our passion for and dedication to raising money for the NRECA International Foundation’s rural electrification efforts in developing countries has only doubled.

On the six-hour, unpaved drive back to the airport, we rode through the rural villages of Arusha. We passed “houses” so dilapidated I had trouble believing families could find shelter from the elements there, let alone know how electricity could change their lives. In 2016, NRECA reported that only 10 percent of rural Africa’s population have access to electricity.

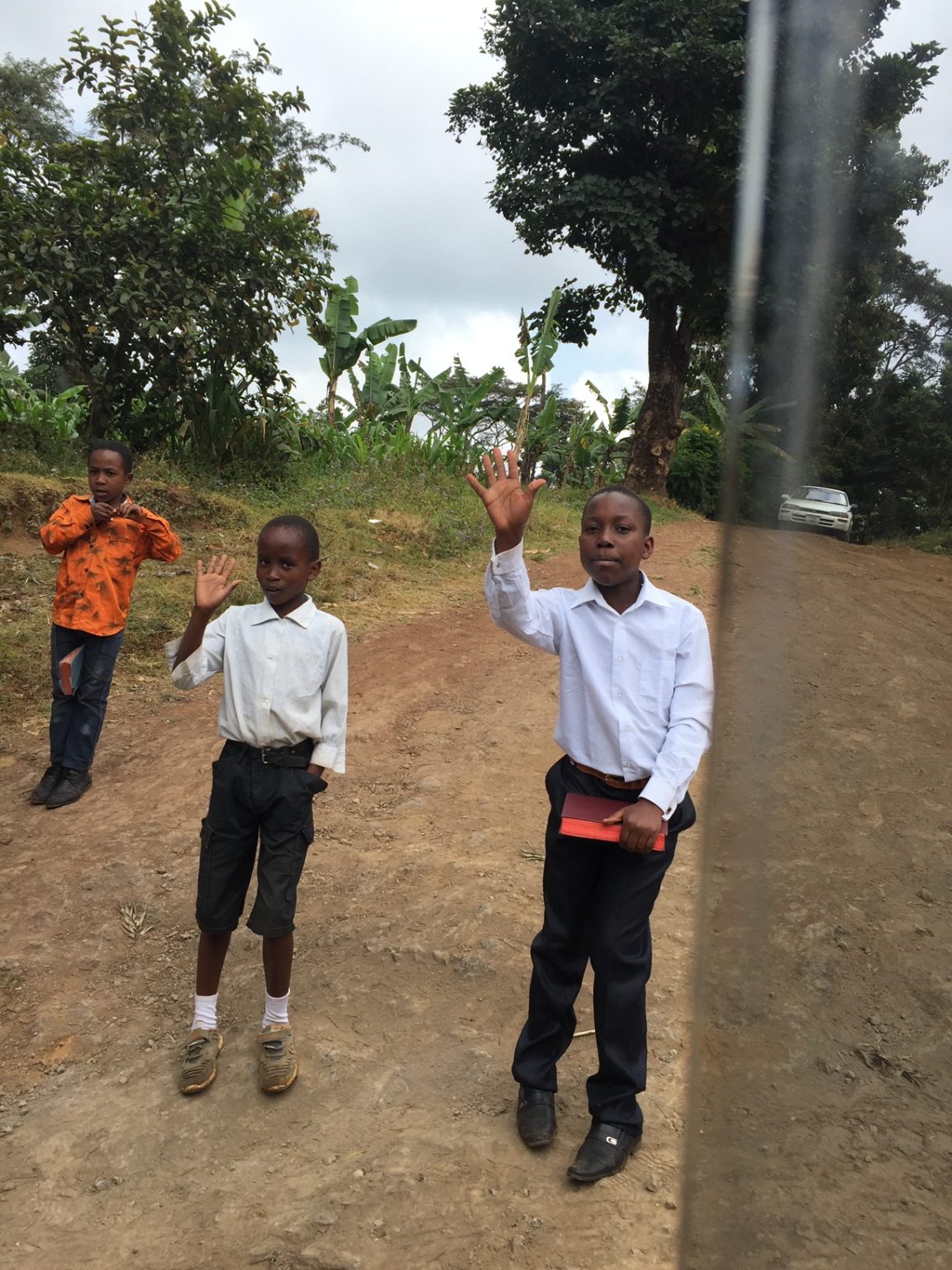

Smack-dab in the middle of nowhere, dust upon dust and miles from any practical buildings, thin children in rainbow clothing ran out to smile, hoot, and wave at us. It nearly split my heart in two.

Thanks to generous donors across the country, I’m grateful to say we’ve raised about $36,800 for rural electrification. We surpassed our original goal by nearly $7,000, but we’re not ready to call it quits. We want to hit the $40,000 benchmark.

There are people in the dark all around the globe (as of 2016, 940 million people were without electricity to be precise), so every donation counts.

Climbing Kilimanjaro was thrilling, but the best part is yet to come; the improved standard of living that results when electric poles are set and power lines are strung in impoverished villages before wide-eyed children and grateful parents.

I started this trip knowing I wanted to raise money to help Africans. But now I’ve returned knowing whose lives I want to electrify — and that makes all the difference.

***

Ready to make a difference? To donate to NRECA International’s Rural Electrification efforts, click here.

***

This article was written by Samantha Kuhn (formerly Samantha Rhodes) on Oct. 31, 2016, and originally appeared in County Living (now Ohio Cooperative Living) magazine, the statewide publication mailed monthly to 300,000+ members of Ohio electric cooperatives. You can read the original story as it was published here at www.ohioec.org.